Health systems build order sets into their electronic health record (EHR) systems with the intent of creating efficiency and reducing variation of ordering practices between providers. When healthcare practitioners use order sets but then add further independent orders, or disregard the order set altogether, it’s imperative to find out why.

Our Phrase Health team examined the metric of “number of orders placed outside of an order set within five minutes” across multiple healthcare systems in order to explore what it could reveal related to the cost and quality of health service delivery.

Why Orders Placed Within Five Minutes

The goal of an order set is to give the ordering practitioner an efficient, thorough view of their options for moving forward with patient care within a clinical workflow for a disease state. Clinical subject matter experts work with EHR builders to create order sets that are easy to use, evidence-based, and fit within a specific workflow. When a clinician uses an order set on a patient, but then immediately proceeds to order additional independent orders on the same patient, it can signal a failure in the design of the order set. This failure opens the health care system up to quality and safety risks, additional costs, and excess clicks for the clinician.

OUR ANALYSIS

In our analysis, we reviewed the number of orders placed outside of an order set within five minutes. This metric can be used to describe an order set or a group of order sets by evaluating the ordering variation occurring outside of order sets. Health systems can use this metric to streamline clinician ordering by ensuring appropriate orders are included in order sets and identifying when ordering is deviating from clinical guidelines.

We’re looking to identify order variation from order sets or other groups of orders that are designed for use across diseases, conditions, or specific clinical quality measures.

EXAMPLES FROM HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS

Among the health systems hosting their data with Phrase Health, we have discovered instances where an analysis of the “orders placed within five minutes” metric shows an opportunity for quality improvements and cost savings. The following are two examples.

Example 1: Not Seeing the CBC Test

A large community health system looked at the “orders placed within five minutes” metric to discover several opportunities to streamline Complete Blood Count (CBC) lab ordering for its providers. The analysis team noticed that several of the health system’s inpatient order sets appeared to be inefficient, including an adult sepsis order set. Thousands of CBC orders were being placed immediately after the order set was utilized.

The thousands of CBC orders placed outside of order sets originally perplexed the team because these order sets contained CBCs within them. However, on further investigation, the team identified that the order sets were relatively long and included many drop-down menus that made it difficult for providers to quickly locate a CBC test. It was buried.

Since they couldn’t find the CBC test, practitioners were placing an order for it separately, outside of the order set. The team recognized that locating the CBC test in a more obvious spot would make it more likely that clinicians could find it and select it within the order set.

EXAMPLE 2: REDUCING ALBUTEROL ORDERS

A quality improvement (QI) team at an academic, tertiary medical center wanted to improve their bronchiolitis pathway to reduce albuterol ordering based on updated guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics. Bronchiolitis accounted for $1.73 billion in hospital charges in the United States in 2009, so there were both financial and clinical imperatives to address any over-utilization of a medication.

The team noticed that despite albuterol being purposefully excluded from their bronchiolitis order set, based on the updated recommendations, clinicians were frequently leaving the order set to place an order for it soon after. To address this issue, the team added the albuterol order into the order set with a message discouraging its use and citing best practice guidelines. This “do not order” approach ended up being an effective way to reduce albuterol orders for patients coded with a discharge diagnosis for bronchiolitis.

FURTHER EXPLORATION

In addition to assisting specific healthcare teams, the Phrase Health team completed a Benchmarking Report based on EHR data from a wide variety of healthcare systems. Within that report, we discovered the following insights into the relative efficiency of order sets across certain conditions and diseases.

SEPSIS AND VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM (VTE) VS. MIGRAINES

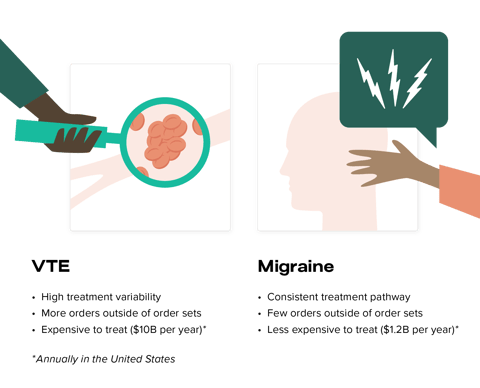

Sepsis and venous thromboembolism (VTE) are costly to treat, and the order sets associated with them are frequently mentioned as a high priority for health systems to optimize. Sepsis and VTE cost the United States (US) healthcare system $24B and $10B per year, respectively, with sepsis being the single most costly condition in the US. We have noticed in our review of EHR data that, in the treatment of these complex conditions, providers often order beyond the order sets. Compare that complexity and cost to the relatively inexpensive treatment of migraine. We have found that the order sets for migraines are usually used efficiently, with few “within five minutes” orders.

CANCER SCREENINGS

Quality measures that are ambulatory focused, like cancer screenings, frequently have high ordering from outside of order sets. This could be because they are often tacked on to appointments for other conditions, since a patient is in the clinic and available to be screened. Therefore, the practitioner is in one order set then quickly adds a cancer screening order separately afterwards. That said, there could be other reasons. Due to the challenges for health systems in standardizing care across outpatient clinics, higher ordering variation could actually signal significant opportunity across health systems for workflow to be standardized through order sets. At a minimum, the high number of additional orders for cancer screenings outside of order sets highlights an area for further data analysis.

FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Data-driven QI teams often review “orders placed within five minutes” metrics and ask if there are specific targets they should be hitting for their order sets. While benchmarking may help, the metric is ultimately most useful at identifying gaps in care versus creating specific recommendations.

For instance, although a CBC order may be placed within five minutes 10 percent of the time, that doesn’t necessarily mean it should be in an order set. Teams will need to decide what the right threshold is on a case-by-case basis.

Similarly, the aim for a health system isn’t to reduce its “orders within five minutes : orders placed from order sets” ratio to “0.” No two patients are identical and they present with complexity that may not fit cleanly within a generalized protocol and workflow. However, by benchmarking your order sets’ performance relative to other health systems, your team can have more informed conversations about what is acceptable ordering variation in support of clinical quality measures.

SUMMARY

As health systems look for efficiencies and ways to improve the quality and safety of patient care, orders placed outside of an order set is a metric that can yield useful insights.

There are differences in information gained from the metric, based upon the complexity of the pathway for a certain condition, and each situation should be addressed individually. In some cases, the order set must be restructured to serve providers better. In other cases, providers may require direct messaging around best practices to ensure consistent care. In addition to reviewing the relevance of orders, the mandatory order set review requirements provide a prime opportunity to focus on performance optimization as well.

ADDITIONAL PHRASE HEALTH REPORTS